Hi everyone, I posted here a long time about an alternate transliteration to Jyutping, called Tone Letter Cantonese. My goal was to create a system that is a lot more linguistically aesthetic, intuitive, and efficient than Jyutping, by changing tone handling and letter assignments. After getting some feedback, I’ve vastly changed the alphabet, and now I’m presenting something that I feel is much more complete than what I presented a year ago. So before I get easily dismissed, I’ll preemptively respond to a very common response…

“We don’t need yet another Romanization system. Jyutping is fine, and it’s the most commonly used.”

Just because Jyutping is the most commonly used, that doesn’t mean it has its flaws. Perhaps one of the reasons why there are so many Romanization systems is that there hasn’t been one that hit the spot? While Jyutping is the most accepted, it is still not standard everywhere, with Yale coming up often, and then most of all, just arbitrary “romanizations” in casual use due to lack of knowledge. Pinyin was very efficient, effective, and well promoted. It is universal and well-understood. Jyutping, while promoted, does not enjoy widely understood use. What I’m promoting here is a Romanization that is efficient and effective as pinyin, and brings some changes to the table that Jyutping does not. Since I mentioned flaws, here are some:

1. Some of the letters are not intuitive. I know that comparisons are made with European languages for J, but the only major one that has that pronunciation is German. The IPA also uses it, but the IPA is not a language. And there’s Latin, which is dead. The Latin-based language most associated (and by law) with Cantonese is English, and the use of J for /y/ would be confusing to your average English, Cantonese, AND international speaker, especially when it is extremely similar to the sound used by Z. Z is similar, but not as bad because /z/ does not exist in Cantonese, so there is less room for confusion. It is also similar to the sound it’s assigned to (I also use the letter j for something else anyways). Contrast the letter confusion in Jyutping to romaji and pinyin, where the former is completely based on English sounds (i.e. no confusion), and the latter is intuitive as mainly the “odd” English letters (x and q, mainly) just need to be relearned (i.e. minimal confusion, and the letters represent sounds relatively unique to Mandarin anyways).

2. Jyutping represents tones with numbers (or it’s also correct to say it has no alternative way to represent tones). First, this is very confusing to people who don’t know each tone number. It is also incredibly unintuitive as these are just numbers and don’t provide any kind of cue. Secondly, it has poor aesthetics. As far as I know, very few other languages use actual numbers to represent the tones within a transliterated script. Numbers are meant to be symbols representing actual numerical values, not be complete substitutes for linguistic phonology, and by doing so, it just looks ugly. Pinyin uses diacritics. Vietnamese uses more. Hmong and Zhuang use actual letters at the end of words. As it is, the use of numbers at the end make jyutping in this form look like just a purely academic rendition of the language that resembles the way we try to Romanize Ancient Egyptian.

So with those flaws in mind, I wanted to try and develop a Romanization that would address those and add more to be a more flexible system. Please give it a read before dismissing it. This is what I came up with:

![]()

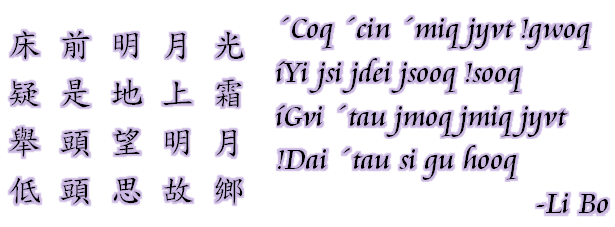

Before I explain the letters, here is a preview of what it looks like first, from Li Bo’s famous poem:

![]()

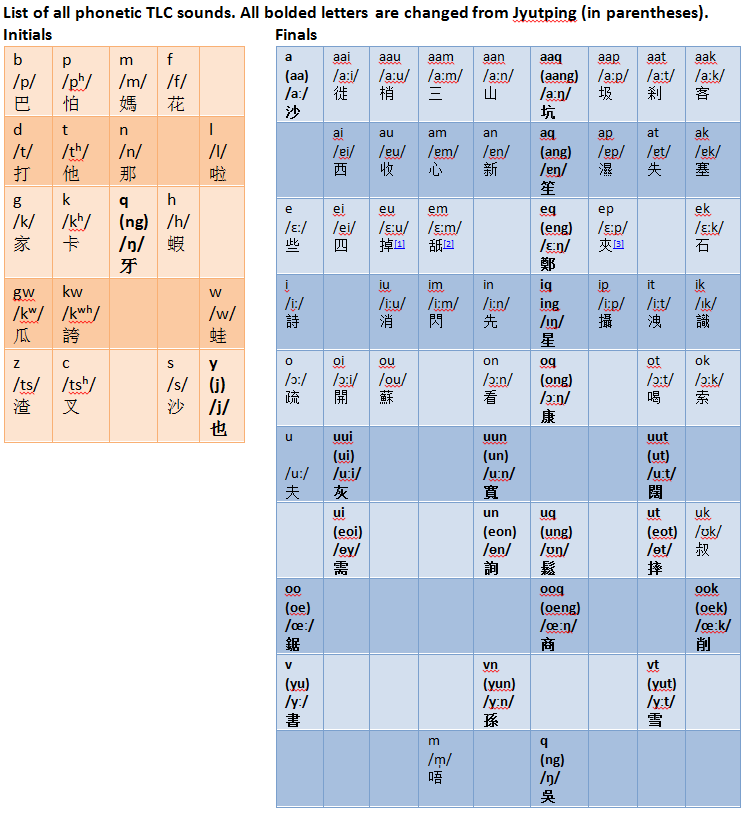

The 28 letters of the TLC alphabet are: A B C D E F G H I K L M N Q O P S T U V W Y Z ! í ` ‘ j

Note that there is only ONE non-standard letter, which is í, which is very accessible.

The alphabet is fairly similar to Jyutping. The biggest phonetic change involved the Jyutping letters: oe, eo, and u (roughly, but not exactly, changed into oo, u, and uu). Two digraphs (NG and YU) are turned into single letters (Q and V, respectively). J is turned back into Y. Finally, the biggest change is the addition of tone letters, which precede each word or syllable/”character.” So with that, here are the improvements I aim to add:

Letter efficiency – TLC does away with three (or five) digraphs (two letters representing one sound), changes one, and adds one new one. This is to keep everything more concise. For example, “Jyutping” itself is now just spelled “Yvtpiq.”

Tone placement – This is something unique to TLC. While the use of letters themselves are not new (Hmong and Zhuang use letters), the placement of the tone letter at the beginning of each word is. And I honestly don’t see how this wasn’t thought of before. Syllables read in an order our brain can properly process: initial consonant, vowel(s), and final consonant in that order. D-O-G. The sounds come out for dog in that order. Now that we add tone to the picture, which had not been designed for any language using the Latin alphabet, linguists decided to throw them at the end. This does not make sense, because I do not pronounce the sounds first and then change my tone to reflect that. The brain does not work that way. First, I need to know how I will be intonating. THEN with tone contour in mind, I utter the sounds. The current way of doing it, bla2 bla5 bla3 bla1 bla2 bla1, is very back and forth and does not flow well between mentally reading and actually pronouncing it. Even 2bla 5bla 3bla 1bla 2bla 1bla reads and flows much better, despite being gibberish.

Tone letters – The idea of using tone letters isn’t new. Like I said above, Hmong and Zhuang use letters, and even Jyutping uses numbers for “letters.” So I won’t say too much. I do think using letters is better for Cantonese than using diacritics for tones like Pinyin and Vietnamese do. The main reason is that there are too many tones, which would translate into too many unique characters being used. Some romanizations that try to use diacritics are just impossible to write (Penkyamp, for example). Also diacritic tones tend to be ignored when typing, so using letters make them more accessible. Finally, as I also mentioned before, I prefer using actual letters or letter-like symbols (as I do for half of the tones) purely because of aesthetics. It’s better to have something isn’t so discordant like numbers are, and I hope you’ll appreciate the reasoning for my tone letters so that even they don’t stick out too much (which I did by choosing all narrow characters)

Ease of typing – Why did letter efficiency matter so much before? Well not only are words shorter, but they would be much easier to type, which is also very important, especially for IMEs.

I’ll only address the changes from Jyutping here.

Phonetic Letters

A – As a final and by itself only, represents /aa/. Otherwise the same.

Q /ŋ/ – “ng” in Jyutping. This may seem like my oddest choice, but I have always felt that in English and Mandarin, it is okay that the sound “ng” is relegated to a digraph. However, for Cantonese, it is such a common sound that it’s important enough to warrant its own letter. Q is a flexible letter because different languages use it for different sounds (especially Mandarin pinyin), and it is not a stretch for most people, because Q normally is pronounced as [k], which is the same location (back of the mouth) as [ŋ]. Random note: Fijian also uses Q for [ŋ]!

Y /j/ – “j” in Jyutping – Cantonese is not Latin or German. Actually, since it has no natural connections to any language that uses the Roman alphabet, the closest language it’s related to is English for historical and modern reasons. English (also the most international language) uses Y for /j/. Even Mandarin pinyin uses Y for /j/. Likewise, Japanese and Korean do too. There’s no need to confuse learners, both native Cantonese speakers and Cantonese learners. Even native German/Swedish/Polish speakers should have no problem with this switch.

V /y/ – “yu” in Jyutping. One thing I never understood about Jyutping is why two letters, “yu,” were needed to pronounce a single sound, especially when Y is not used for anything else (why not “Jytping”?). Anyways, I’ve converted that into the nice and easy “v.” Not only is it often used as a substitute for the same sound in pinyin, it is similar to a u in appearance as well. Note that in Latin, V was also a vowel (since it was U), so v being a vowel is not something that’s unheard of.

Oo /œː/ – “oe” in Jyutping

U /ɵ/, /ʊ/ – “eo” and “u” in Jyutping, respectively. Also as a final and by itself only, /u:/

Uu /uː/ only (no longer /ʊ/)

By coincidence, u now resembles the “short U” from English, and uu is the “long U.” While I could have stuck with the Jyutping “oe,” I went with “oo” to keep in pattern with the other double letters (aa, uu), where each of those are individual sounds. “oe” gives the impression of a diphthong, while “oo” makes it clear that while there are two letters, it’s one sound.

I made a huge departure here from most systems. Instead of the “u” (/uː/ +/ʊ/ ) and “oe/eo” (/œː/ + /ɵ/) as two different groups, I took out the /ʊ/ and /ɵ/ parts and merged them into a separate group, as they are actually very close in pronunciation. Using the single “u” for them is also very intuitive. In fact, while “oe/eo” (/œː/ + /ɵ/) have been grouped together, they don’t really sound alike (the only thing they had in common were vowel sounds foreign to Mandarin).

All these changes are summarized in these tables:

![]()

Tone Letters

Finally, the other big component of this alphabet, and what sets it apart from Jyutping. Like Jyutping, the TLC alphabet does not use the entering tones. Unlike Jyutping, each tone is represented by a letter rather than a number, and it is positioned at the BEGINNING of each word/character. This positioning made the most sense to me because tones at the end of words come too late in reading to make it smooth. It is okay word for word like a dictionary, but when you start to read sentences, it is extremely awkward. I would rather know the tone first before pronouncing the sound. My belief is that the current way of sticking the tone at the end is an awkward Western mechanic because Western languages aren’t used to tones.

With the larger variety of vowels and more tones compared to Mandarin, pinyin’s (and also Yale Romanization’s) diacritic approach can’t be used without making the system much more cumbersome and unwieldly. So the best solution is that each tone is its own letter.

陰平 Tone 1: ! (Because this appears at the beginning of each word, it cannot be confused with an exclamation point: “`M!goi!”)

陰上 Tone 2: í – can be typed as r or / for IME or casual use.

陰去 Tone 3: (no letter) – can be typed as x when needed to be explicit. The letter i, semicolon ; and hyphen - are also acceptable.

陽平 Tone 4: `

陽上 Tone 5: ´ – the normal apostrophe ' can also be used, despite it being vertical.

陽去 Tone 6: j

Each letter does NOT have a capitalized form (even if all other letters are capitalized, these stay the same!). These letters are anything but arbitrary. I wanted characters that were as narrow as possible so as to not detract from the “sound” letters. I also needed letters that were very common, even if they were not one of the standard 26 letters. That led me to these 6 letters, and each of them has a good reason for them. I’ll start backwards, from tone 6. j has the low hook, indicating a low tone. The other two low tones (4 and 5) have appropriate stroke directions, so they are self-explanatory. Although tone 4 can be flat (and is described as such), it can also go down. While tone 2 has the same inflection as tone 5, it is “on a stick,” indicating that it’s a higher tone. Likewise, tone 1 is also a stick (high tone), but also “!” fits perfectly with the first tone, because its pronunciation tends to be a little “louder!” Furthermore, each flat tone (for the sake of argument, tone 6 is flat) also has a dot in it as well. Finally, tone 3 is the most neutral, and therefore, it is the one with no letter (often it’s either tone 3 or tone 6 that seems to get this treatment).

So with all that said, here’s another example. In standard Omniglot style, I’ll use an excerpt from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights Excerpt:

![]()

Jyutping:

Jan⁴jan⁴ saang¹ceot¹lai⁴ zau⁶hai⁶ zi⁶jau⁴ ge³, hai² zyun¹jim⁴ tung⁴ kyun⁴lei⁵ soeng⁶ jat¹leot⁶ ping⁴dang². Keoi⁵dei⁶ geoi⁶jau⁵ lei⁵sing³ tung⁴ loeng⁴sam¹, ji⁴ce³ jing¹goi¹ jung⁶ hing¹dai⁶gaan¹ ge³ gwaan¹hai⁶ lai⁶ wu⁶soeng¹ deoi³doi⁶.

TLC:

`Yan`yan !saaq!cut `lai jzaujhai jzi`yau ge, ‘hai !zvn`yim `tuq `kvnílei jsooq !yatjlut `piqídaq. ‘Kuijdei jgui‘yau ‘leisiq ‘tuq ‘looq!sam, ‘yice !yiq!goi jyuq !hiqjdai!gaan ge !gwaanjhai jlai jwu!sooq duijdoi.

(toneless - for practice just reading the phonetics)

Yanyan saaqcut lai zauhai ziyau ge, hai zvnyim tuq kvnlei sooq yatlut piqdaq. Kuidei guiyau leisiq tuq looqsam, yice yiqgoi yuq hiqdaigaan ge gwaanhai lai wusooq duidoi.

It may take some adjusting to, but after a little exposure, it becomes much more efficient to read, especially with tones. Any thoughts are welcome!

ALSO: Cantonese Characters 粵字 (jYvtjzi, Yvtzi)

This is actually a completely separate thing, but this is just another idea I had. So in the scenario where I had complete control over linguistics, TLC would be the Romanization arm. The other arm would be to fix the Chinese characters themselves, which while used, are heavily out of favor. In fact, many of them aren’t even able to be displayed easily on the computer. And many of the ones that are are incredibly cumbersome to write or bother to learn.

So my idea was to take a page out of Korean (and to a lesser extent, Japanese) and create a system for native Cantonese words. These 粵字 (Yvtzi) are characters made up of Chinese three Chinese radicals: a tone, an initial, and a final. For example, 王 would be the component for the final –oq (as the original word was `woq). To actually make the word `woq, another radical for the initial ‘W’ would be added, and finally a tone radical,刂(tone 4) would be added. Note that while I use this example, `woq would actually NOT need a separate character, as it is standard to both written and spoken Cantonese. These characters would only be used for spoken Cantonese (much like the current characters are).

Overall, there would be 56 finals, 19 initials, and obviously 6 tones, making it a very finite number of characters to learn (80). Note that all tone radicals would be very simple. One of them would already be the radical口, which is used in every Cantonese character. For Yvtzi, it would represent tone 3. 亻would be tone 2 due to the direction and height of the stroke. Initial radicals would be simple as well (although not as simple), and all of them would require the ability to be easily added to the final. All the finals would be representative of their sound, and would be relatively simple too, in terms of stroke count (like王).

Overall, I think this is a very Chinese way of implementing a character-based phonetic system, rather than using other methods.

Again, this is just an idea I had (and in a sense, it kind of contrasts with Enigmatism's proposed Jyutzyu), and I haven’t fleshed out all the characters, so if anyone likes it, you’re welcome to expand on it.

“We don’t need yet another Romanization system. Jyutping is fine, and it’s the most commonly used.”

Just because Jyutping is the most commonly used, that doesn’t mean it has its flaws. Perhaps one of the reasons why there are so many Romanization systems is that there hasn’t been one that hit the spot? While Jyutping is the most accepted, it is still not standard everywhere, with Yale coming up often, and then most of all, just arbitrary “romanizations” in casual use due to lack of knowledge. Pinyin was very efficient, effective, and well promoted. It is universal and well-understood. Jyutping, while promoted, does not enjoy widely understood use. What I’m promoting here is a Romanization that is efficient and effective as pinyin, and brings some changes to the table that Jyutping does not. Since I mentioned flaws, here are some:

1. Some of the letters are not intuitive. I know that comparisons are made with European languages for J, but the only major one that has that pronunciation is German. The IPA also uses it, but the IPA is not a language. And there’s Latin, which is dead. The Latin-based language most associated (and by law) with Cantonese is English, and the use of J for /y/ would be confusing to your average English, Cantonese, AND international speaker, especially when it is extremely similar to the sound used by Z. Z is similar, but not as bad because /z/ does not exist in Cantonese, so there is less room for confusion. It is also similar to the sound it’s assigned to (I also use the letter j for something else anyways). Contrast the letter confusion in Jyutping to romaji and pinyin, where the former is completely based on English sounds (i.e. no confusion), and the latter is intuitive as mainly the “odd” English letters (x and q, mainly) just need to be relearned (i.e. minimal confusion, and the letters represent sounds relatively unique to Mandarin anyways).

2. Jyutping represents tones with numbers (or it’s also correct to say it has no alternative way to represent tones). First, this is very confusing to people who don’t know each tone number. It is also incredibly unintuitive as these are just numbers and don’t provide any kind of cue. Secondly, it has poor aesthetics. As far as I know, very few other languages use actual numbers to represent the tones within a transliterated script. Numbers are meant to be symbols representing actual numerical values, not be complete substitutes for linguistic phonology, and by doing so, it just looks ugly. Pinyin uses diacritics. Vietnamese uses more. Hmong and Zhuang use actual letters at the end of words. As it is, the use of numbers at the end make jyutping in this form look like just a purely academic rendition of the language that resembles the way we try to Romanize Ancient Egyptian.

So with those flaws in mind, I wanted to try and develop a Romanization that would address those and add more to be a more flexible system. Please give it a read before dismissing it. This is what I came up with:

Before I explain the letters, here is a preview of what it looks like first, from Li Bo’s famous poem:

The 28 letters of the TLC alphabet are: A B C D E F G H I K L M N Q O P S T U V W Y Z ! í ` ‘ j

Note that there is only ONE non-standard letter, which is í, which is very accessible.

The alphabet is fairly similar to Jyutping. The biggest phonetic change involved the Jyutping letters: oe, eo, and u (roughly, but not exactly, changed into oo, u, and uu). Two digraphs (NG and YU) are turned into single letters (Q and V, respectively). J is turned back into Y. Finally, the biggest change is the addition of tone letters, which precede each word or syllable/”character.” So with that, here are the improvements I aim to add:

Letter efficiency – TLC does away with three (or five) digraphs (two letters representing one sound), changes one, and adds one new one. This is to keep everything more concise. For example, “Jyutping” itself is now just spelled “Yvtpiq.”

Tone placement – This is something unique to TLC. While the use of letters themselves are not new (Hmong and Zhuang use letters), the placement of the tone letter at the beginning of each word is. And I honestly don’t see how this wasn’t thought of before. Syllables read in an order our brain can properly process: initial consonant, vowel(s), and final consonant in that order. D-O-G. The sounds come out for dog in that order. Now that we add tone to the picture, which had not been designed for any language using the Latin alphabet, linguists decided to throw them at the end. This does not make sense, because I do not pronounce the sounds first and then change my tone to reflect that. The brain does not work that way. First, I need to know how I will be intonating. THEN with tone contour in mind, I utter the sounds. The current way of doing it, bla2 bla5 bla3 bla1 bla2 bla1, is very back and forth and does not flow well between mentally reading and actually pronouncing it. Even 2bla 5bla 3bla 1bla 2bla 1bla reads and flows much better, despite being gibberish.

Tone letters – The idea of using tone letters isn’t new. Like I said above, Hmong and Zhuang use letters, and even Jyutping uses numbers for “letters.” So I won’t say too much. I do think using letters is better for Cantonese than using diacritics for tones like Pinyin and Vietnamese do. The main reason is that there are too many tones, which would translate into too many unique characters being used. Some romanizations that try to use diacritics are just impossible to write (Penkyamp, for example). Also diacritic tones tend to be ignored when typing, so using letters make them more accessible. Finally, as I also mentioned before, I prefer using actual letters or letter-like symbols (as I do for half of the tones) purely because of aesthetics. It’s better to have something isn’t so discordant like numbers are, and I hope you’ll appreciate the reasoning for my tone letters so that even they don’t stick out too much (which I did by choosing all narrow characters)

Ease of typing – Why did letter efficiency matter so much before? Well not only are words shorter, but they would be much easier to type, which is also very important, especially for IMEs.

I’ll only address the changes from Jyutping here.

Phonetic Letters

A – As a final and by itself only, represents /aa/. Otherwise the same.

Q /ŋ/ – “ng” in Jyutping. This may seem like my oddest choice, but I have always felt that in English and Mandarin, it is okay that the sound “ng” is relegated to a digraph. However, for Cantonese, it is such a common sound that it’s important enough to warrant its own letter. Q is a flexible letter because different languages use it for different sounds (especially Mandarin pinyin), and it is not a stretch for most people, because Q normally is pronounced as [k], which is the same location (back of the mouth) as [ŋ]. Random note: Fijian also uses Q for [ŋ]!

Y /j/ – “j” in Jyutping – Cantonese is not Latin or German. Actually, since it has no natural connections to any language that uses the Roman alphabet, the closest language it’s related to is English for historical and modern reasons. English (also the most international language) uses Y for /j/. Even Mandarin pinyin uses Y for /j/. Likewise, Japanese and Korean do too. There’s no need to confuse learners, both native Cantonese speakers and Cantonese learners. Even native German/Swedish/Polish speakers should have no problem with this switch.

V /y/ – “yu” in Jyutping. One thing I never understood about Jyutping is why two letters, “yu,” were needed to pronounce a single sound, especially when Y is not used for anything else (why not “Jytping”?). Anyways, I’ve converted that into the nice and easy “v.” Not only is it often used as a substitute for the same sound in pinyin, it is similar to a u in appearance as well. Note that in Latin, V was also a vowel (since it was U), so v being a vowel is not something that’s unheard of.

Oo /œː/ – “oe” in Jyutping

U /ɵ/, /ʊ/ – “eo” and “u” in Jyutping, respectively. Also as a final and by itself only, /u:/

Uu /uː/ only (no longer /ʊ/)

By coincidence, u now resembles the “short U” from English, and uu is the “long U.” While I could have stuck with the Jyutping “oe,” I went with “oo” to keep in pattern with the other double letters (aa, uu), where each of those are individual sounds. “oe” gives the impression of a diphthong, while “oo” makes it clear that while there are two letters, it’s one sound.

I made a huge departure here from most systems. Instead of the “u” (/uː/ +/ʊ/ ) and “oe/eo” (/œː/ + /ɵ/) as two different groups, I took out the /ʊ/ and /ɵ/ parts and merged them into a separate group, as they are actually very close in pronunciation. Using the single “u” for them is also very intuitive. In fact, while “oe/eo” (/œː/ + /ɵ/) have been grouped together, they don’t really sound alike (the only thing they had in common were vowel sounds foreign to Mandarin).

All these changes are summarized in these tables:

Tone Letters

Finally, the other big component of this alphabet, and what sets it apart from Jyutping. Like Jyutping, the TLC alphabet does not use the entering tones. Unlike Jyutping, each tone is represented by a letter rather than a number, and it is positioned at the BEGINNING of each word/character. This positioning made the most sense to me because tones at the end of words come too late in reading to make it smooth. It is okay word for word like a dictionary, but when you start to read sentences, it is extremely awkward. I would rather know the tone first before pronouncing the sound. My belief is that the current way of sticking the tone at the end is an awkward Western mechanic because Western languages aren’t used to tones.

With the larger variety of vowels and more tones compared to Mandarin, pinyin’s (and also Yale Romanization’s) diacritic approach can’t be used without making the system much more cumbersome and unwieldly. So the best solution is that each tone is its own letter.

陰平 Tone 1: ! (Because this appears at the beginning of each word, it cannot be confused with an exclamation point: “`M!goi!”)

陰上 Tone 2: í – can be typed as r or / for IME or casual use.

陰去 Tone 3: (no letter) – can be typed as x when needed to be explicit. The letter i, semicolon ; and hyphen - are also acceptable.

陽平 Tone 4: `

陽上 Tone 5: ´ – the normal apostrophe ' can also be used, despite it being vertical.

陽去 Tone 6: j

Each letter does NOT have a capitalized form (even if all other letters are capitalized, these stay the same!). These letters are anything but arbitrary. I wanted characters that were as narrow as possible so as to not detract from the “sound” letters. I also needed letters that were very common, even if they were not one of the standard 26 letters. That led me to these 6 letters, and each of them has a good reason for them. I’ll start backwards, from tone 6. j has the low hook, indicating a low tone. The other two low tones (4 and 5) have appropriate stroke directions, so they are self-explanatory. Although tone 4 can be flat (and is described as such), it can also go down. While tone 2 has the same inflection as tone 5, it is “on a stick,” indicating that it’s a higher tone. Likewise, tone 1 is also a stick (high tone), but also “!” fits perfectly with the first tone, because its pronunciation tends to be a little “louder!” Furthermore, each flat tone (for the sake of argument, tone 6 is flat) also has a dot in it as well. Finally, tone 3 is the most neutral, and therefore, it is the one with no letter (often it’s either tone 3 or tone 6 that seems to get this treatment).

So with all that said, here’s another example. In standard Omniglot style, I’ll use an excerpt from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights Excerpt:

Jyutping:

Jan⁴jan⁴ saang¹ceot¹lai⁴ zau⁶hai⁶ zi⁶jau⁴ ge³, hai² zyun¹jim⁴ tung⁴ kyun⁴lei⁵ soeng⁶ jat¹leot⁶ ping⁴dang². Keoi⁵dei⁶ geoi⁶jau⁵ lei⁵sing³ tung⁴ loeng⁴sam¹, ji⁴ce³ jing¹goi¹ jung⁶ hing¹dai⁶gaan¹ ge³ gwaan¹hai⁶ lai⁶ wu⁶soeng¹ deoi³doi⁶.

TLC:

`Yan`yan !saaq!cut `lai jzaujhai jzi`yau ge, ‘hai !zvn`yim `tuq `kvnílei jsooq !yatjlut `piqídaq. ‘Kuijdei jgui‘yau ‘leisiq ‘tuq ‘looq!sam, ‘yice !yiq!goi jyuq !hiqjdai!gaan ge !gwaanjhai jlai jwu!sooq duijdoi.

(toneless - for practice just reading the phonetics)

Yanyan saaqcut lai zauhai ziyau ge, hai zvnyim tuq kvnlei sooq yatlut piqdaq. Kuidei guiyau leisiq tuq looqsam, yice yiqgoi yuq hiqdaigaan ge gwaanhai lai wusooq duidoi.

It may take some adjusting to, but after a little exposure, it becomes much more efficient to read, especially with tones. Any thoughts are welcome!

ALSO: Cantonese Characters 粵字 (jYvtjzi, Yvtzi)

This is actually a completely separate thing, but this is just another idea I had. So in the scenario where I had complete control over linguistics, TLC would be the Romanization arm. The other arm would be to fix the Chinese characters themselves, which while used, are heavily out of favor. In fact, many of them aren’t even able to be displayed easily on the computer. And many of the ones that are are incredibly cumbersome to write or bother to learn.

So my idea was to take a page out of Korean (and to a lesser extent, Japanese) and create a system for native Cantonese words. These 粵字 (Yvtzi) are characters made up of Chinese three Chinese radicals: a tone, an initial, and a final. For example, 王 would be the component for the final –oq (as the original word was `woq). To actually make the word `woq, another radical for the initial ‘W’ would be added, and finally a tone radical,刂(tone 4) would be added. Note that while I use this example, `woq would actually NOT need a separate character, as it is standard to both written and spoken Cantonese. These characters would only be used for spoken Cantonese (much like the current characters are).

Overall, there would be 56 finals, 19 initials, and obviously 6 tones, making it a very finite number of characters to learn (80). Note that all tone radicals would be very simple. One of them would already be the radical口, which is used in every Cantonese character. For Yvtzi, it would represent tone 3. 亻would be tone 2 due to the direction and height of the stroke. Initial radicals would be simple as well (although not as simple), and all of them would require the ability to be easily added to the final. All the finals would be representative of their sound, and would be relatively simple too, in terms of stroke count (like王).

Overall, I think this is a very Chinese way of implementing a character-based phonetic system, rather than using other methods.

Again, this is just an idea I had (and in a sense, it kind of contrasts with Enigmatism's proposed Jyutzyu), and I haven’t fleshed out all the characters, so if anyone likes it, you’re welcome to expand on it.